App Where You and Friends Can Roll D20

You've just been through a bad breakup. After a few days of sulking, you decide it would be best to get out of the house. So you head to your favorite bar, hoping that the comfortable, familiar surroundings will help lift your spirits. Just as you're about to open the door, your phone buzzes in your pocket. "Warning," an alert tells you, "your ex is inside."

Most social discovery sites, like Foursquare or Highlight, are so eager to connect you with people that they can cross the line from useful to creepy. But what if these services are asking the wrong question? Like decimated reality aggregators, maybe social discovery shouldn't just be about who you want to meet, but also about what you might want to avoid. That's the premise behind three new apps that promise to help us stay away from uncomfortable people and situations.

Existential iPhones

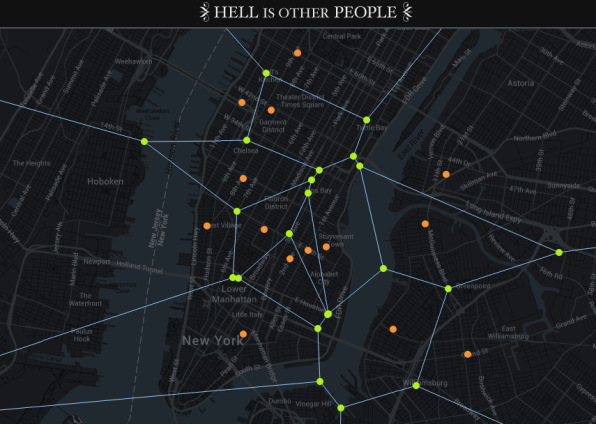

In Jean-Paul Sartre's 1944 play Huis Clos ("No Exit"), three sinners visit the existentialist version of the afterlife, where they must spend an eternity in a room with individuals they can't even stand for five minutes. The play ends with the line "Hell is other people." Scott Garner, a student at New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, used Sartre's quip as the inspiration for an app he calls Hell is Other People.

According to Garner, the app is "partially a commentary on my disdain for 'social media' and partially an exploration of my own difficulties with social anxiety."

Using location-based networking site Foursquare, the app plots friend locations onto an "avoidance map" (powered by Google Maps) so that users can ensure that no one has any uncomfortable run-ins. The app even overlays green "safe distance" zones on the map to help users keep their distance in case someone changes location but forgets to check in.

How Sick Is This?

Garner isn't the only one thinking about using social networks to avoid people. At New York's University of Rochester, a number of researchers, among them Adam Sadilek, created an app called Fount.in, which they claim can be used to forecast the future health of users with an astonishing 91% accuracy. In some ways, Fount.in is reminiscent of Google Flu Trends, except that instead of analyzing troves of long-term data to predict seasonal patterns, Sadilek and his colleagues work in real time, by analyzing users' Twitter messages.

The challenge Sadilek's team faces is turning tweets, which contain lots of noise and missing data, into signals about a user's health. Even doctors are unlikely to tweet something as direct as, "I've just been diagnosed with influenza type A," and the word "sick" can mean different things ("I'm sick with the flu" vs. "This band is sick!" vs. "That movie made me sick!"). In the same way that Google's search algorithms can intelligently discern between "jobs" meaning "Steve Jobs" and "jobs" meaning "employment," Sadilek and his colleagues employ natural language analysis to tease out the semantic nuances of our tweets and combine them with other users' data to build a picture of regional health.

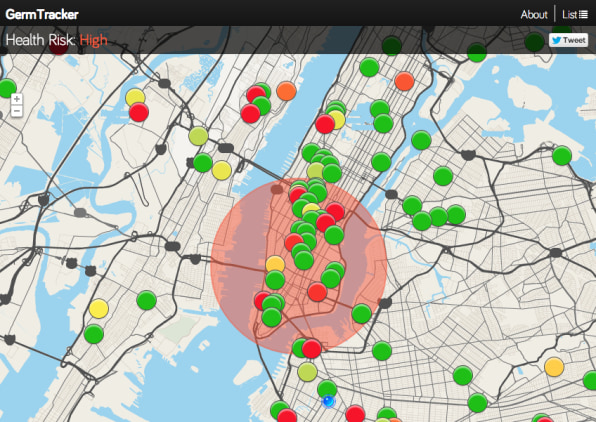

To give an example of how Fount.in works, imagine arriving at the airport to catch a plane. While waiting to board, you send a tweet from your phone, complaining that you were up all night coughing and now feel terrible, just as you're about to leave for vacation. Provided that the tweet is geo-tagged, Fount.in's algorithm can find other people in your physical area who are close enough that they might pick up whichever virus you're carrying. As long as you update your location with some degree of regularity, the algorithm can also tell you roughly how many people carrying the flu virus you have been exposed to over the last week. Sadilek likens it to having "X-ray vision."

If you opt into location tracking, Fount.in's map switches to a local one, showing your location surrounded by a cluster of coloured dots, much like the ones in Hell is Other People. In this case, though, the dots don't indicate the proximity of frenemies, but the likelihood of user sickness, with red indicating the highest chance and green indicating the lowest.

At the moment Fount.in supports 10 cities around the world, with plans to expand that number in future. Since it was predominantly created as a research project (Sadilek is currently employed as a data scientist at Google), the findings were also extrapolated to form the basis of a paper, co-authored earlier this year by Sadilek and Henry Kautz, entitled "Modeling the Impact of Lifestyle on Health at Scale."

The Future Of Social Recommendation

Both of these experiments illustrate how social discovery is starting to branch out from its roots in simply connecting people. Mainstream, consumer-facing product makers are also starting to realize the potential to expand social discovery.

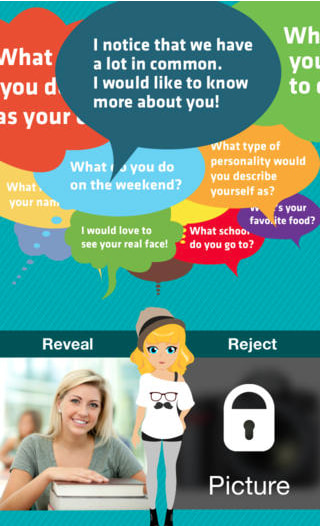

"So far social discovery has been pretty limited to a few categories," says Benjamin Liu, the cofounder of Anomo. His product, a fast-growing and innovative social discovery app, aims to circumvent the creepiness of meeting strangers by encouraging its users to interact with one another prior to meeting using Second Life-style avatars.

"This industry could still evolve pretty significantly," says Liu, "although at the moment it's still mainly business networking or dating."

Given the buzz that ideas like Hell is Other People are generating, that may be about to change. Social discovery might not yet be living up to the groundbreaking innovation shown by its technological big brothers "search" and "social networking," but maybe that's because we just haven't met the right application yet.

[Image: Flickr user Nicki Varkevisser]

App Where You and Friends Can Roll D20

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3015887/anti-social-apps-will-help-us-avoid-our-friends

0 Response to "App Where You and Friends Can Roll D20"

Post a Comment